Hate crime through the Looking Glass

We’ve repeatedly been told that Britain is in the grip of a huge rise in Islamophobic attacks. According to Tell Mama, the group that monitors hate crime against Muslims, anti-Muslim attacks reportedly shot up by 326 per cent in 2015 and spiked again after the Brexit vote last year.

All such hateful crimes and incidents are utterly to be deplored. These statistics, though, have come in for criticism about their methodology and should be treated accordingly with caution. The principal caveats concern the subjectivity of these reports, exacerbated by the presumed echo-chamber effect of such alarmism which encourages some people wrongly to perceive themselves as victims.

None of this, though, captures the utterly surreal, Alice Through the Looking Glass madness of the official police recording of Islamophobic hate crime which has been unearthed by Hardeep Singh of the Network of Sikh Organisations. Through a Freedom of Information request, he obtained from the Metropolitan Police a breakdown of the “victims of Islamophobic hate crime” for 2016.

This showed a total of 1227 recorded Islamophobic attacks. But here’s the thing: of these victims, only 912 were Muslim. Of the other victims of supposedly anti-Muslim hate crime 39 were “Christian”, 19 were Hindu, 11 were atheists, seven were agnostic, four were Sikh, two were Greek Orthodox, two were Roman Catholic, two were Jewish and one was a Buddhist. Of the remainder 86 were “unknown”, 85 were “blank” and 57 victims weren’t contacted.

So how can it possibly be that so many victims of anti-Muslim hatred aren’t Muslim at all? The answer lies in the bizarre way the police define hate crime in general. The Met say: “An Islamophobic Offence [sic] is any offence which is perceived as Islamophobic by the victim or any other person, [my emphasis] that is intended to impact upon those known or perceived to be Muslim.”

Eh? What this tortured last bit seems to mean is explained more fully by the

College of Policing’s “Hate Crime Operational Guidance”. This similarly lays down that “the perception of the victim, or any other person (see 1.2.4 Other person), is the defining factor in determining whether an incident is a hate incident, or in recognising the hostility element of a hate crime.”

What section “1.2.4 Other person” says, by way of elucidation, is that this other person might be a police officer, a witness, a family member, “civil society organisations who know details of the victim, the crime or hate crimes in the locality, such as a third-party reporting charity”, a professional who supports the victim, “someone who has knowledge of hate crime in the area – this could include many professionals and experts such as the manager of an education centre used by people with learning disabilities who regularly receives reports of abuse from students”, or a “person from within the group targeted with the hostility”.

So it’s not just the subjective opinion of the victim that is to define hate crime, but anyone from this panoply of individuals too. The guidance also states that the victim doesn’t actually have to be from any of the listed victim groups; a hate crime is committed merely if the attacker intended to target one of those groups.

But how would anyone know, if a Sikh or Hindu or Catholic or Jew was attacked, that their attacker actually intended to attack a Muslim but got it wrong? Are we to believe that in all 87 of these “Islamophobic” attacks on Christians, Sikhs, Hindus etc the attacker shouted something hateful about Muslims?

No matter! The police don’t want actual facts. The guidance goes on: “The victim does not have to justify or provide evidence of their belief, and police officers or staff should not directly challenge this perception. Evidence of the hostility is not required for an incident or crime to be recorded as a hate crime or hate incident.”

So whether or not a crime is actually a hate crime doesn’t depend upon any objective test. Perish the thought that the police might value such evidence!

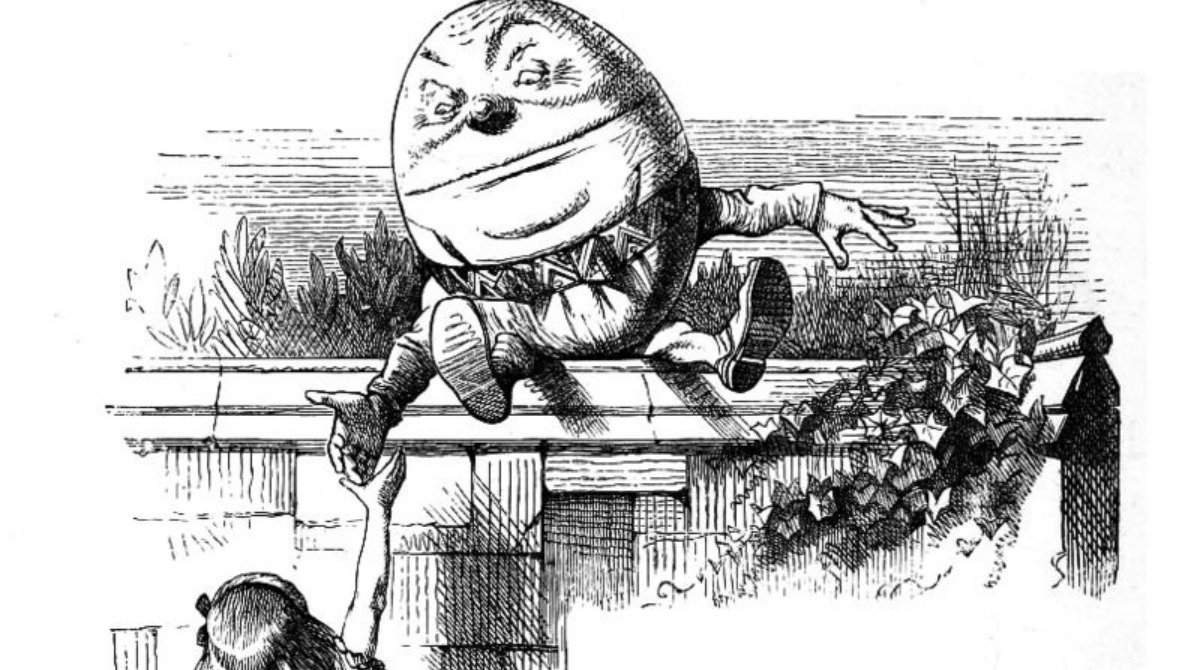

As Humpty Dumpty might have said, had Lewis Carroll been sufficiently politically correct: “When I use the phrase hate crime, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”