Our irreproducible humanity

Leaders of the museum and art gallery world have suggested that reproductions of artistic masterpieces should be put on display while the originals are stored out of sight. This would preserve such treasures from deterioration or the risk of theft, while enabling the public to view great works which are deemed too fragile to be displayed.

Neil MacGregor, the former director of the British Museum and the National Gallery, says modern reproduction techniques could enable people to see, for example, The Family of Darius Before Alexander by Paolo Veronese with its true, unfaded colours. “Technology could give us for the first time the experience the artist intended us to have.”

This is an intriguing concept. The notion that a reproduction can be better than the actual work painted by the artist challenges our belief in the value of authenticity.

Of course, the point is that deterioration over time means we don’t see the actual colour of the picture as painted. Nevertheless, what is the more valuable experience: looking at the original painting with its faded colours, or a reproduction with the colour enhanced? Would we think a forgery of a Rembrandt, a Velasquez or a Constable has as much merit as the originals, if not more?

A similar issue arises from the use of Zoom, FaceTime and other social media platforms to communicate with the world during this period of lockdown and social isolation. These have proved a lifeline for keeping connected to family and friends, or holding virtual meetings that have enabled many to keep working.

And yet such engagement at a distance comes at a cost. For all Zoom’s undoubted benefits, many have found using it a disconcerting or emotionally tiring experience. It’s not just that it constrains spontaneity through the invasive scope of the camera or microphone. It also deprives us of the innumerable different cues that we constantly absorb about each other in real-life encounters.

We don’t just see or hear things. We also touch, taste, smell them, which we obviously can’t do in virtual encounters. Our senses, moreover, are all crucial to how we perceive ourselves. They help form the essential me-ness of being “me”. And that isn’t reproducible.

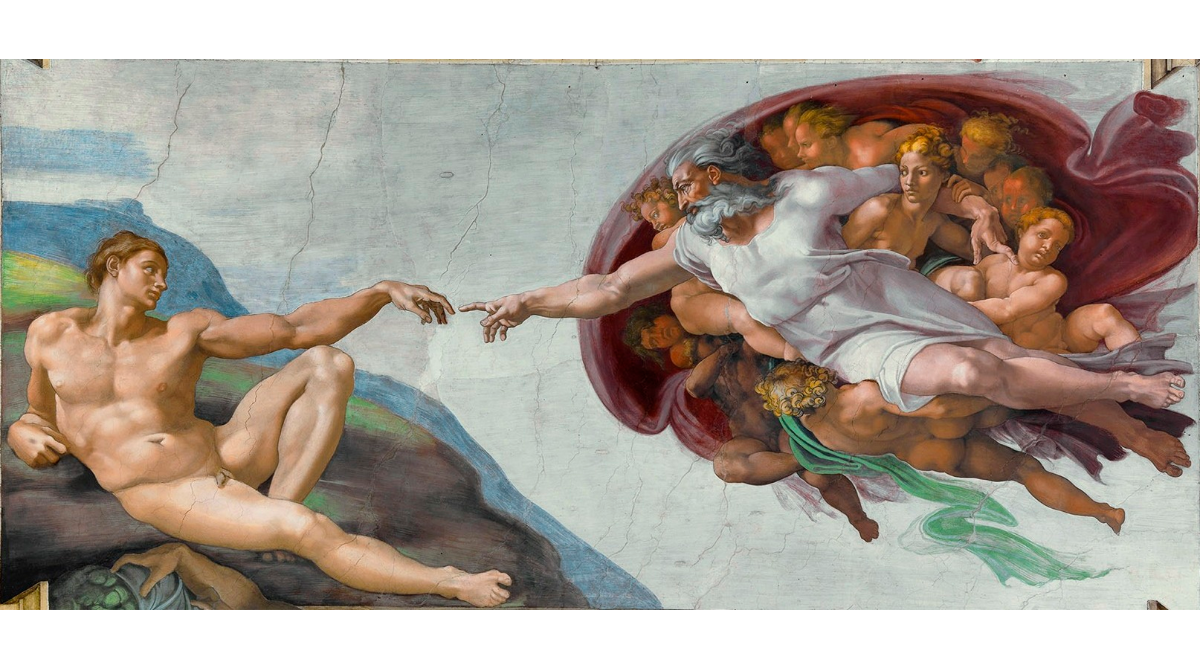

It’s why ceremonies on Zoom that are invested with emotional significance, such as weddings, funerals or proposals of marriage, aren’t as fulfilling as the real thing. And it’s why a reproduction of a Veronese painting can’t give us the unique essence that illuminates the work from within.

When this Covid nightmare eventually passes we may find that, far from continuing unthinkingly to embrace an artificially manufactured world, we will have rediscovered and reaffirmed what it is to be a human being.

To read my whole Times column (£), please click here.